The two’s complement representation was invented to achieve a critical goal in computer hardware: to perform subtraction using the very same circuitry designed for addition. This unification saves physical space on the chip and reduces design complexity. To appreciate the elegance of this solution, we must first examine the less efficient methods it superseded: signed magnitude and one’s complement.

Signed Magnitude Link to heading

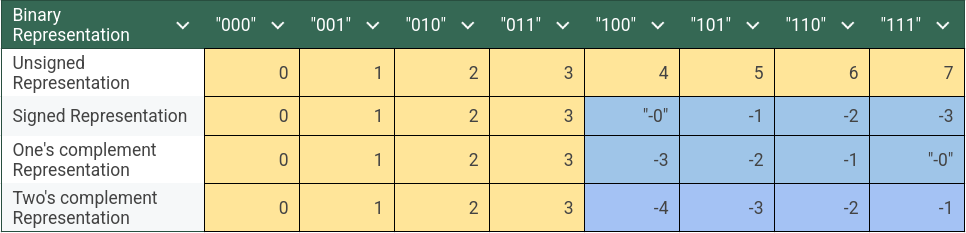

It is the simplest form because we use the Most Significant Bit to represent the sign i.e. 0 for positive and 1 for negative and rest of the bits represent the magnitude. The first problem that we can see is presence of both positive and negative zeroes which wastes a representable value and complicates comparisons. Also, the logic circuit for addition and subtraction would need to be different as well.

$3 = 011$

$-3 = 111$

One’s Complement Link to heading

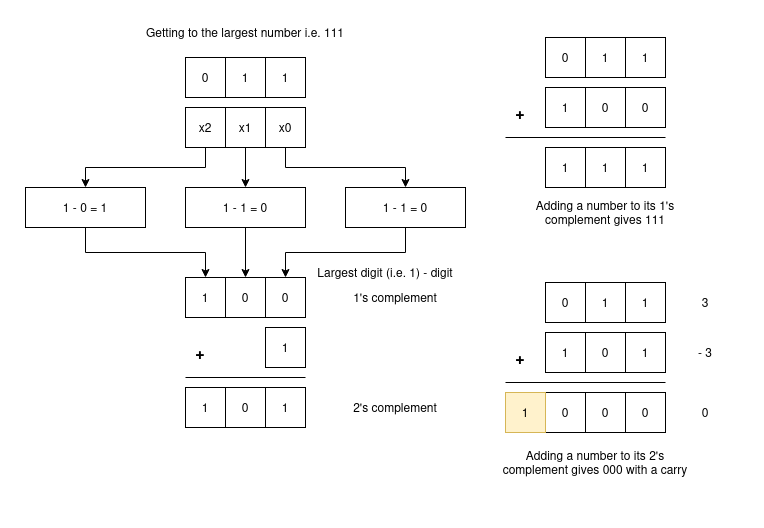

What about one’s complement? What does it mean? So, by the terminology we can see that it represents the remainder after we take away a given digit (0 or 1) from the largest digit i.e. 1. In short, its just $(1 - digit)$. 1’s complement is a form of diminished radix complement for binary number system (base=2 i.e. two unique digits). Radix means base of number system (number of unique digits) and diminished radix complement means the remainder after taking away digits from (base - 1 i.e. largest digit in the number system). The main essence of one’s complement or any other diminished radix complement is that if you add a number to it’s diminished radix complement, you get the result of largest digit in all places, for example for 3-digit binary number, it would be 111, and for 3-digit decimal number it would be 999. Looking at the issues of 1’s complement, the issue of +0 and -0 persists and still we need some extra logic for performing subtraction.

1’s complement of $011$ = $100$

Two’s Complement Link to heading

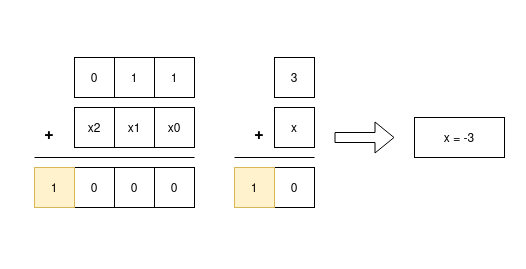

Now, the final boss: 2’s complement comes in. Suppose, I have a number say 3 and add it to another number x and the result comes out to be 0. Then, x is definitely the number -3. In other words, x is the radix complement of the number 3.

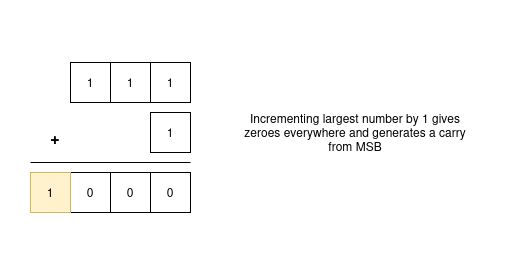

If I want to perform subtraction by means of addition, then definitely the result would always come out to be bigger but we have fixed number of digits decided beforehand. So, taking advantage of this fact, if we add 1 to the largest number say 111 for 3-digit binary, then we will get 1000 i.e. all 3 digits will be zero and there will be a carry. The generated carry will be discarded in a fixed-width system. And, how do I get to 111? By adding a number to its 1’s complement. So, what is 2’s complement? It is the incremented value of 1’s complement i.e. (1’s complement + 1). This thought process is the heart of binary arithmetic.

The two’s complement divides the number line into two halves where one half represents positive numbers from $0$ to $(2^{n-1} - 1)$, and the other half represents negative numbers from $-2^{n-1}$ to $-1$. But, in each half if we move from left-to-right, the value keeps getting larger.

2’s complement of 0010 = 1110

2’s complement of 0111 = 1001

ALU Design Link to heading

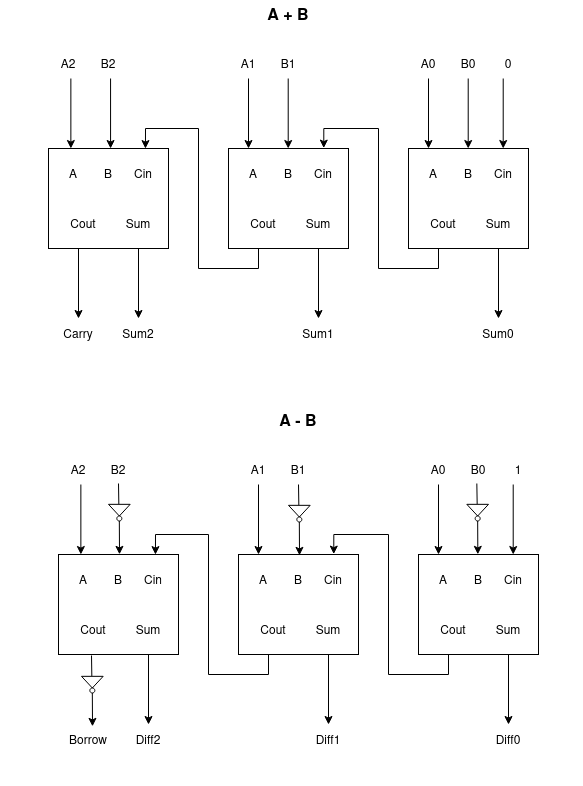

While designing ALU for binary arithmetic, we can use the same series of full-adders for A+B and A-B. For addition, set Cin = 0 for LSB’s full adder and inputs are fed as it is. For subtraction, set Cin = 1 for LSB’s full adder and the second input is bitwise negated before feeding into full adders. Symbolically,

$$ A - B = A + (\text{\textasciitilde}B) + 1 $$